Poet. Feminist. Activist.

These are the three words I chose to identify myself on my “business” card. I realize the “f” word, not to mention the “a” word, is polarizing and might turn some people off, but then those people are not likely to enjoy my poetry. In fact, I was recently told that my poetry and the National Organization for Women (NOW) where I was a board member were too “aggressive” for a self-described women’s empowerment group that invited me to read at their event. They didn’t think my poem about Cinderella ditching the glass slippers and becoming a feminist was empowering or humorous. Honestly, I thought it was one of the least “offensive” poems I could have recited:

After

the wedding they never dance again

. . .

She sells the slippers on e-bay, goes back to school

for a degree in Women’s Studies,

and writes a second book on feminist philosophy:

How to Survive Happily Ever After.

Readers often assume I’ve worked in women’s services or have a Women’s Studies Degree. Neither is true, though I do think that some university should award me an honorary degree. As the oldest daughter of a teenage (sometimes single) mother, I had a front row seat to the difficulty of trying to survive as a woman under the patriarchy. I wish I could say my mother modeled how to resist and break free. Instead, I learned what not to do if I wanted to break the cycle and become an independent woman.

Some of my earliest memories are of crying “That’s not fair,” and my mother asking in response “Who told you life was fair?”

I always had an innate awareness of all the ways the world was unjust; particularly to women.

In college, I took a course on Women and the Law at Stony Brook University. This is my origin story: it confirmed and made explicit what I had always intuitively known about the patriarchal structure of society and institutional gender-based oppression. I acquired the framework and language with which to more articulately express the many injustices imposed on everyone who isn’t a hetero, cisgendered, white man.

At poetry readings, I’m sometimes asked how I know so much about social injustice, gender discrimination, and violence against women. I give the traditional answer about the vocation of the poet (with a twist). Writers are always advised to pay attention. We usually interpret this to mean pay attention to trees and birdsong, but I pay attention to society. I write from my life, the lives of women I know, the lives of women I’ve read about, the world I exist in.

I practice empathy and use my imagination to write the truth.

Poetry has space for all kinds of poets: nature poets, lyric poets, narrative poets, and activist poets. All those subjects and voices are valid and worthy. They all seek to preserve some truth, and, even when the truth is ugly, poets can use beautiful language to convey that truth. John Keats’s lines are still relevant today: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—” Robert Frost paid attention to rural life in New England. Ada Limón pays attention to horses and her Latinx heritage. I pay attention to social injustice and write poems about it.

Does writing about social justice make a difference? Poet Steven Clifford has asked me (and others) “Can poetry change the world?” I’m still looking for an honest and meaningful way to answer that question. What can my Cinderella poem do today (besides make a group of women at high tea uncomfortable)? Can it feed the hungry? Ensure equal pay and access to healthcare? End discrimination, genocide, and war? Can you get the news from it? Not according to William Carlos Williams who wrote: “It is difficult to get the news from poems . . .” So what can we do? We can bear witness. Salman Rushdie (who knows first-hand the power and danger of wielding language) writes: “We can sing the truth and name the liars.”

Because abusers rely on the silence of their victims, speaking out is a profound act that lets women know they aren’t alone, encourages empathy, and builds community.

Sometimes that community is tangible. I create space and gather poets at the open mic that I host for the Babylon Village Arts Council at Jack Jack’s Coffee House in Babylon, NY (join us on the first Thursday of every month). Sometimes that community is virtual. After Roe v. Wade was overturned, NOW’s Suffolk, NY chapter responded by organizing a virtual poetry reading in support of women’s reproductive rights. I invited over a dozen poets to read. Some of them I knew personally. Many I had never met other than between the pages of an anthology we were published in (Choice Words: Writers on Abortion, Haymarket Books). Almost every one of them participated in the reading.

W. H. Auden wrote “For poetry makes nothing happen.” I disagree. My bio reads: “Her work explores the intersection of poetry and activism.” Initially, that referred to the subjects I wrote about. However, during my term as Poet Laureate of Suffolk County, NY (June 2023-2025), I moved activism off the page and into the streets (well, more accurately, into a coffee shop, a bookstore, and a farm) with events called Poetry in Action. With the help of the community and poets Rosa Todaro, Lisa James, and Steven Clifford, I organized two fundraisers for local charities, a volunteer event at a local non-profit farm, and a get out the vote postcard writing night. Poetry made something happen at these events: it brought people together to celebrate poetry and serve the community.

Sometimes the impact is less visible. I have many poems about breast cancer and have learned it is a radical act to write openly and honestly about cancer (particularly cancer of the breast; an external gender marker). But every time I read those poems, at least one woman in the audience connects with me to ask how I am, or to thank me for writing about cancer, or to share her own experience with illness. Recently a young woman said she had a lump in her breast and had been wondering if it was okay to write about it. I assured her that it was and encouraged her to do so. Maybe my reading made that one woman feel less alone and more empowered. Does that change the world? I’ll never know, but it’s meaningful to the two of us, and who knows how that small exchange may reverberate across the universe. (Update: as I was drafting this, that woman wrote and published the essay she was unsure about writing).

Silence is a tool of the patriarchy. Silence about discrimination, abuse, assault, or illness isolates and shames us. Poet Muriel Rukeyser wrote in her poem titled “Käthe Kollwitz”: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? / The world would split open.” Let’s all continue to speak the truth. Let’s all stay aware. Pay attention. Bear witness. Write. Read poetry out loud in public spaces. Let’s keep telling the truth and trying to split this world open.

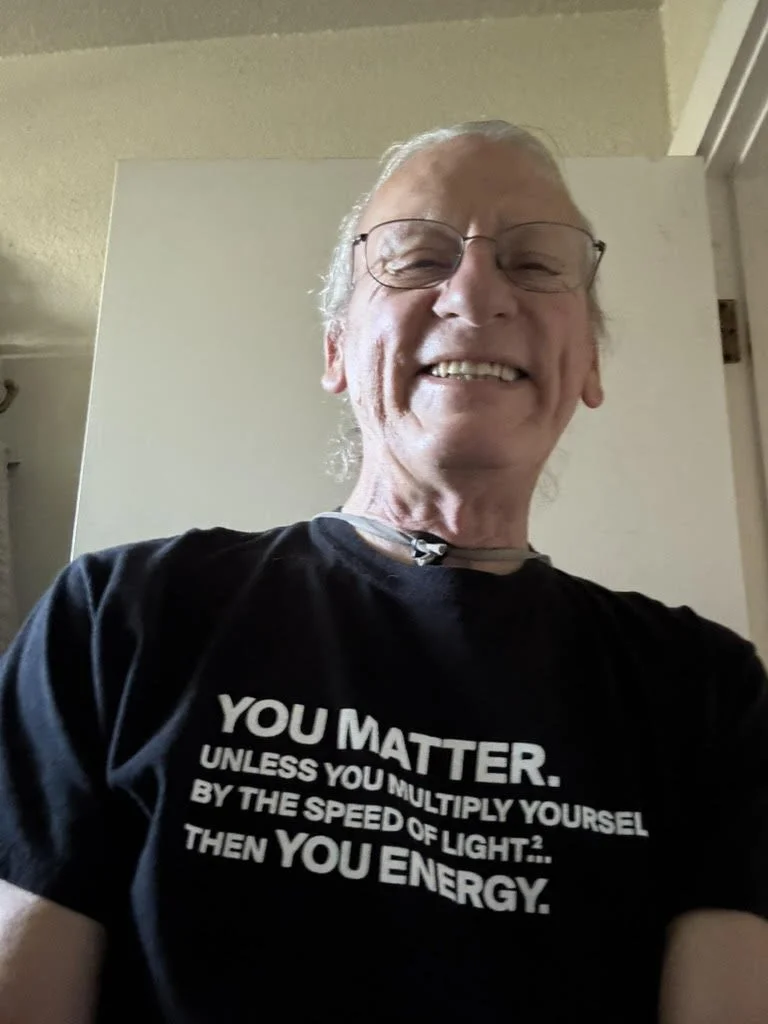

Deborah Hauser

is the author of Ennui: From the Diagnostic and Statistical Field Guide of Feminine Disorders (Finishing Line Press). Her poems and book reviews have appeared in Ms. Magazine, Women’s Review of Books, The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Bellevue Literary Review, Calyx, and Academy of American Poets Poem-A-Day, and elsewhere. Her work explores the intersection of poetry and activism.

She has taught literature and writing at Stony Brook University and Suffolk County Community College. She curates and hosts a monthly poetry reading series at Jack’s Coffee House for the Babylon Village Arts Council, has served as Secretary and Board Member of the Suffolk County Chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW), and is on the board of the Long Island Poetry & Literature Repository. She leads a double life on Long Island where she works in the insurance industry and served as Poet Laureate of Suffolk County, NY (2023-2025).

G&E In Motion does not necessarily agree with the opinions of our guest bloggers. That would be boring and counterproductive. We have simply found the author’s thoughts to be interesting, intelligent, unique, insightful, and/or important. We may not agree on the words but we surely agree on their right to express them and proudly present this platform as a means to do so.